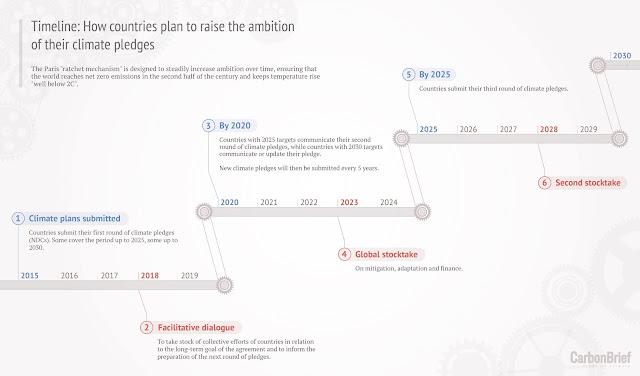

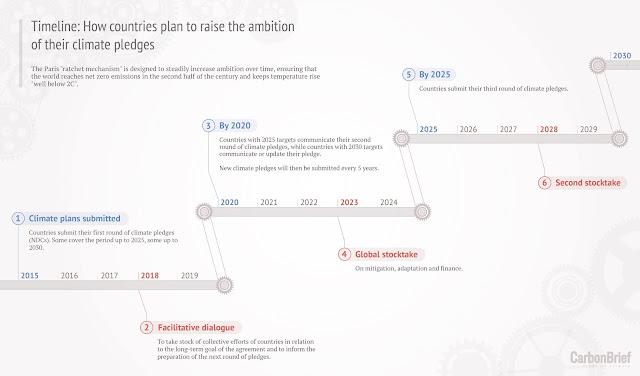

The Paris Ratchat Mechanism is designed to steady increase ambition over the time , Ensuring that world reaches net zero emission in the second half of the century and keeps temperature 'well below 2 C '.

Stage one: NDCs 1.0

Even though the agreement has not yet come into force, this cyclical process is already underway.

In the nine months before Paris, countries submitted their “intended nationally determined contributions”, which are regularly abbreviated to INDCs.

Each of these contains the country’s intended domestic target for reducing or slowing its greenhouse gas emissions. Others contained information on topics, such as adaptation, loss and damage and financial need, according to individual preference.

The 160 submissions received by the UN remain “intended”, and are not set in stone until the country in question ratifies the agreement. Indeed, many countries stressed that their contribution was contingent upon the outcome of the UN deal struck in Paris.

Countries are not legally bound to meet the targets in their nationally determined contribution (NDC), but they must take action “with the aim of achieving” their goals.

However, the current policies do not collectively achieve the agreement’s aim to keep temperature rise to below 2C — and are even further from its aspirational target of limiting it to 1.5C.

Stage two: Facilitative dialogue

The ratcheting up of ambition really begins in 2018, when countries have agreed to convene a “facilitative dialogue”.

This is a chance for countries to take stock of how close they are to achieving the long-term goals of the agreement to peak emissions as soon as possible and achieve net zero emissions in the second half of the century.

This dialogue is designed to inform the next round of NDCs, so that countries have a clearer idea of the direction of travel.

Stage three: NDCs 2.0

With the outcome of the facilitative dialogue in mind, countries have to either update or communicate a new NDC by 2020.

Due to the flimsy set of rules guiding the first round of NDCs, the submissions cover various timeframes. Some set a target for 2030, such as the EU. Others have a target for 2025, such as the US.

For countries with a target covering the period up to 2025, they must communicate a new NDC by 2020. For those with 2030 targets, they must “communicate or update” these by 2020.

The agreement says that the efforts of each country will “represent a progression over time”, and reflect its “highest possible ambition”. For developed countries, these should be economy-wide, absolute emission targets, while developing countries are encouraged to move towards this kind of target over time. The division between developed and developing countries is now more fluid than it was before the agreement.

This does not mean that the ambition contained within each country’s current NDC is frozen in place. The agreement says that a country can adjust its contribution “at any time…with a view to enhancing its level of ambition” — but there is no strict obligation to undertake such improvements.

Once the agreement has come into force, countries will agree a common timeframe for their future contributions. This means that future cycles will eventually fall into line, with every country setting targets covering the same time period.

Countries must thereafter continue to submit new NDCs every five years. Alongside these, they are also encouraged to submit an “adaptation communication”, which includes its priorities, plans and needs. Every two years, developed countries also have to communicate how much climate finance they will provide to developing countries.

Stage four: Global stocktake

In 2023, just before the third round of NDCs are due to be submitted, the UN has agreed there will be a “global stocktake”.

0 comments:

Post a Comment